(LYDIA CHEBBINE FOR THE 19TH; GETTY IMAGES)

By Jasmine Mithani

Originally published by The 19th

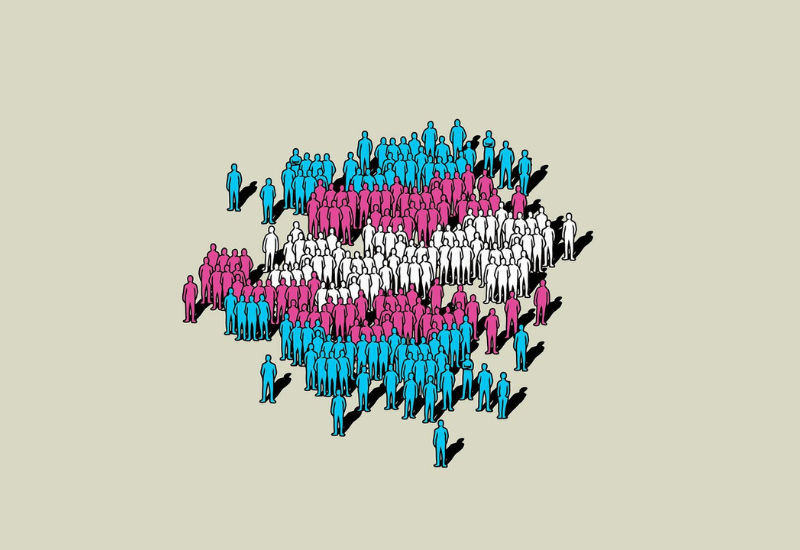

The 2022 U.S. Trans Survey aims to be the largest population survey of transgender Americans ever. The online survey, a project of the National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE), opened to the public in October. Over 33,000 people have pledged to complete the survey before it closes December 5.

The first iteration of the U.S. Trans Survey (USTS) was fielded in 2015 and was the largest population research project focused solely on trans people. The reports and secondary analyses stemming from the sample of 27,715 trans people across all states and territories provided invaluable data about the lives of trans people. It saw over four times as many respondents as its precursor, the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, fielded in 2008 and 2009.

The 19th sat down with Dr. Sandy E. James, the lead researcher for the 2022 USTS, to talk about the state of data on transgender Americans and the implications of this study. James was also the research director at National Center for Transgender Equality, the advocacy nonprofit running the USTS, in 2015 and was the lead author on the 2015 report.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jasmine Mithani: What sort of data gaps are there when it comes to information about trans people? What does it look like if you’re trying to find data on trans populations in the United States?

Dr. Sandy E. James: I mean, it’s scant. There’s very little data out there. When people think about data about what’s going on for people in the United States, there are some go-to surveys. Many of them are federal surveys, others large national surveys. We can’t identify disparities, because those data collections at this time, by and large, are not collecting information that will allow them to identify trans people. So there are massive gaps.

I do want to be clear that the USTS aims to fill many, many of those gaps in collecting data, but there are some things that we can’t say. This is not a survey that is counting or giving us prevalence information about trans people. We’re not in this survey [trying] to give a population estimate.

But we’re able, particularly with the large datasets that we had last time in 2015 and then we expect to have again this year, to say a whole lot about trans people as a whole across the nation. We can also talk about people’s experiences by state, we can talk about people’s experiences by race, or lots of other demographic characteristics like disability or age.

What did you prioritize including in this 2022 survey?

There’s a lot of things we really got right in 2015. [But] there’s always room for improvement. We wanted to start with those items that we knew were very important for us to focus on. We want to be able to talk about income, employment, housing, any kind of social determinants of health, really — big health measures and the things that drive those. We wanted to be able to focus on those still, as we did last time.

The other things we had to prioritize — it’s really important for us to think about the context of the times in which we are living. When we fielded the last survey it was August, September 2015. If you remember, [from] 2016 onward there was just a proliferation of anti-trans legislation, whether it be bathroom bills, now onto medical care. It’s just been an onslaught for years. We wanted to consider all of that.

Another big thing that nobody expected was COVID. The 2015 survey [questions] relied very heavily on experiences you had in the last year, or experiences you had in the last 30 days, or experiences you had interacting with people. So when we were designing the survey, this time, we really had to think about that context. Were people out and about in the same way? Were people wearing masks? What does that do if somebody is not identifying you or labeling you as trans — how does that change the way you interact?

You mentioned the rising anti-trans rhetoric, but also a lot of protections have been passed in recent years in some areas. How do you anticipate that will be reflected in the responses, if at all?

It’s difficult to know. As I mentioned, in 2015, things did look stark. And that was an environment where we didn’t have a constant onslaught of this anti-trans rhetoric, but beyond just rhetoric, actual legislation. We do expect to see that showing up.

It frankly shows up in the ways in which people have varying levels of comfort even taking the survey. I’ve noted people are more concerned about who’s collecting the data and where it’s going to go. It’s all valid.

But what we’ve seen based on the collection so far is this incredible resiliency. That’s something that we also wanted to capture more of. What kind of experiences of resiliency and positive life course experiences could we capture this time that we didn’t capture last time? We want to be able to paint a full picture of trans lives, right? A 360 view of trans life, not just like a narrow slice of what’s going on.

But we do expect changes. I don’t expect them to be for the better. It might be that things stay the same. But things were stark last time. I don’t expect to see large improvements in that.

What steps have you and the NCTE taken to build trust with people taking the survey?

We have tried as best we could to convey that this is a community-led survey by trans people for trans people. It’s really important to convey that this time around NCTE partnered with some phenomenal organizations, Black Trans Advocacy Coalition, TransLatin@ Coalition and the National Queer Asian Pacific Islander Alliance. And presenting this as partners I think goes a long way to building trust with people.

There is also, of course, the data security pieces. An Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviews, approves, and monitors research involving people and ensures that their rights and welfare are protected. This is a [University of California, Los Angeles] IRB-approved survey, we’ve also taken some extra steps to make sure that we are being good stewards of people’s data. We obtained the National Institutes of Health Certificate of Confidentiality which further protects people’s data and ensures that nobody can be forced to disclose information that might identify people in any federal, state or local civil, criminal, administrative, legislative or other proceedings, for example, if there is a court subpoena.

This is not a survey in which you could identify people from the information that we’re asking. And we take that incredibly seriously, it’s an anonymous survey. We’re not keeping data so that we can identify people, we’re aggregating it so that we can report on experiences of people in aggregate.

We really have to acknowledge this is a scary time for people, I think it would be foolish not to. And it’s completely understandable. We take seriously the responsibility for caring for people’s data, and making sure that they are secure when they are taking the survey.

How will this data be used beyond the reports that your organization generates? How was the 2015 data used?

[The 2015 data is] still cited heavily now. It showed up in Supreme Court filings. You’ve seen it used in Supreme Court arguments. We’ve seen it used in federal and state courts.

We’ve seen it show up in advocacy, for example, in statehouses and in Congress, we’ve seen advocates be able to talk about experiences that trans people have and use USTS data to be able to bring those experiences to life and quantify some of what’s going on.

One example I have of that is being able to use it in the state of Maryland when they were trying to adopt an X gender marker in the statehouse. We’re able to talk about data about how people need IDs that align with their identities.

Sometimes [for grants] you have to be able to show a need. So this data has been used to be able to show needs and be able to actually apply for and get funding to keep programs going.

How does the survey fit into the current ecosystem of population research like the American Community Survey?

What we are able to do is say, OK compared to the other populations, let’s look at the trans population. So for example, in 2015, we were able to say the poverty rate for trans people in our sample was twice the rate in the U.S. population. So that’s how it fits in. By using measures that have been validated, and are widely used across federal surveys, we can say, OK, we calculated the unemployment rate at this particular time, here’s what it was in the U.S. population and here’s what it was in our sample.

We’re able to fill in those gaps and say, hey, now we have information about what’s going on for trans people. Now let’s do something about it. What policies do we need to put into place to help to resolve these? And if there are policies in place, how can we make sure the implementation is working towards a certain end?

What can be accomplished now that there are multiple years of quantitative data to complement what you know about people’s lived experiences?

I think it’s also really important to understand that the word you used was correct. Quantitative data complements. It doesn’t supplant, it doesn’t supersede; it complements the information we have about stories and lived experience. That’s really, really important.

Now that you have information that you can put in front of people to say, this is not just [affecting] one person, we’re not just talking about a random person who you’ve never met, we’re talking about large percentages. They can actually start to see that these stories bring the numbers to life.

In the last survey, we had a map that shows where trans people in the sample were and it maps on directly to the geographic distribution of people in the United States. So now we’ve quantified it, we’ve put it out there, we’ve plotted it on a map — you can’t say that trans people only live here or there. They live in every jurisdiction. Every member of Congress has some trans people among their constituents. And when you start to quantify, and when you start to actually put words on paper, it brings those things to life in a way that you can’t, when you’re just saying, “Yeah, well, we know a lot of trans people have this experience.”

It’s not that it’s any more real than it was before, and I don’t want to suggest that it is. But for some people, it becomes a little bit more concrete and easier to engage with and understand and have some perspective on. I think that’s the right way to describe it always: that the quantitative data complements all of those other stories. Those things coexist.

There’s so much good that can come from something like this, but a lot of it does have to do with quantifying discrimination. How can it also be a joyous thing to have this data?

I think it is phenomenal that both last time and what we’re also seeing this time, trans people are making it clear that they have something to say, and they want their voices heard. That is really, really important.

The visibility piece is massive. It might not necessarily mean that [someone] is front and center on Instagram, but these are the voices of trans people that are showing up here. And that counts for a lot.

We wanted to be able to capture more about life experiences, experiences of joy and happiness. It’s hard to do that, quite frankly, quantitatively. We wanted to not just focus on hardship, hardship, hardship all the time. And that was something that we want to be able to really bring to life.

It’s obviously harder, because we’re trying to collect information that shows differences and disparities, but we also want to share similarities. We also want to share joy.

Is there anything else you wanted to say?

I just want to reiterate that what we are trying to do is ensure that we had a community-led survey that people could feel comfortable with and confident in. We’ve tried to do as much as we can to show that — we’re asking a lot of people to trust us. A lot of people have already shown that they have something to say and so we’re very, very thankful and grateful for all the time people have put in so far into it.

We know that we know we have a responsibility here and we take it very seriously. We just can’t thank people enough for the time they’ve taken and everything they’re doing to really make this a success. This isn’t a success if we don’t have respondents, and I can say with confidence that it will be successful. But the work is not done. We’ve got more to do.

The 2022 U.S. Trans Survey is open through December 5 and available in English and Spanish. The survey can be taken on any screen, including a phone, and has been tested for screen-reader compatibility.

Catholic Hospitals Barred from Offering Gender-Affirming Care

Catholic Hospitals Barred from Offering Gender-Affirming Care  Spotlight: Spencer Dean — From Franklin to the Beast’s Castle

Spotlight: Spencer Dean — From Franklin to the Beast’s Castle  Take a Deep Breath — Marriage Equality is Probably Here to Stay

Take a Deep Breath — Marriage Equality is Probably Here to Stay  Supreme Court Asked to Reconsider Landmark Same-Sex Marriage Ruling

Supreme Court Asked to Reconsider Landmark Same-Sex Marriage Ruling  Trans Youth Emergency Project Supports Trans Youth, Families

Trans Youth Emergency Project Supports Trans Youth, Families  Over a Million Queer Women Rely on Medicaid. What Happens If They Lose It?

Over a Million Queer Women Rely on Medicaid. What Happens If They Lose It?