Demonstrators wave pride flags and march in protest of Florida's "Don't Say Gay" bill in St. Petersburg, Florida in March 2022. (MARTHA ASENCIO-RHINE/TAMPA BAY TIMES/AP)

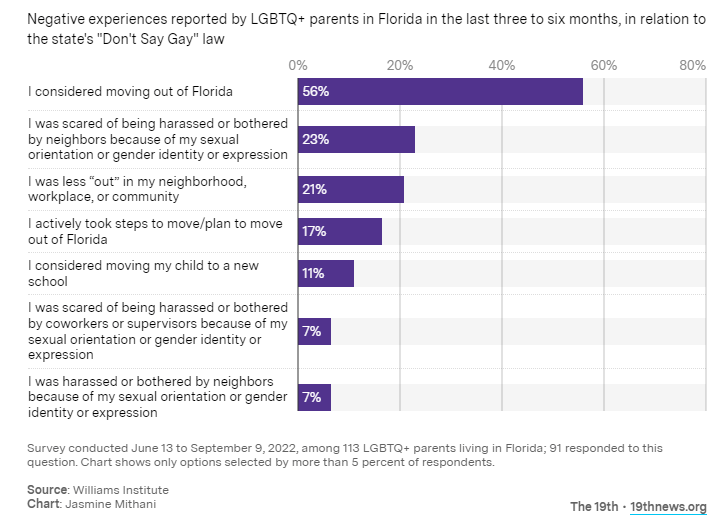

Of the respondents, 17 percent have already taken steps to leave Florida, and 11 percent have considered transferring their children to other schools.

By Orion Rummler, Sara Luterman, Kate Sosin

Originally published by The 19th

One in five parents went back in the closet in some capacity — including some who no longer hold their partner’s hand in public. More than half considered leaving Florida. Nearly nine out of 10 parents said they worried the bill would make their kids less safe.

Those numbers are the stark findings from a study on the effects of Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law just released by the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Law. Unlike much of the reporting around the Parental Rights in Education Act, which went into effect last July, the study focuses solely on LGBTQ+ parents in the state.

Professor Abbie Goldberg of Clark University, who authored the report, said she was moved to conduct the study because so much attention has been paid to queer youth and teachers.

“If you’re 7, you may not know that you are gay, for example, or may not be thinking about your identity in that way,” she said. “But you certainly know that you have two moms, or you have gay moms.”

“Don’t Say Gay” laws date back decades, but have drawn special attention over the last year as 20 states have expressed renewed interest in passing them. The bills are often dubbed as parental rights measures. Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida argues that his state’s law allows parents to regulate what kind of material is appropriate for their children.

Some LGBTQ+ advocates have countered that the law renders queer youth invisible. Goldberg said her research, gathered from June to September last year, found that it erased LGBTQ+ families altogether.

“From a parent’s perspective, it may not even seem like a huge deal when we’re talking about very young children [and sexual orientation and gender],” she said. “But when you’re a parent, and your kid is 3 and they know that they have two moms, there’s no real trapdoor there to say it doesn’t matter.”

Janelle Perez, her wife and their two daughters live in Miami-Dade County. Her older daughter is 5 and attends an Episcopalian school that Perez describes as “very welcoming” to LGBTQ+ families like hers. Because the school is private, it isn’t bound by the new laws.

“It’s very much an active conversation instead of the state being like, ‘You have to do this’,” she told The 19th.

According to Perez, the biggest change since the passage of the Parental Rights in Education Act is the behavior of other parents.

“One parent was a little bit upset that our kids drew a rainbow in their calendars. It was for one of the months in spring. I don’t even think it was June. I don’t know if that would have happened before. That’s just where the rhetoric is in Florida. To kids, it’s just a rainbow,” she said.

Todd Delmay, his husband and their son live in Hollywood, Florida. Delmay owns a travel agency and recently became the executive director of the Southern Most HIV/AIDS Ride, the second-largest HIV/AIDS cycling fundraiser in the United States.

Delmay’s son attends public school. Books have been quietly removed from the school shelves, including “Red: A Crayon’s Story.” In the story, a blue crayon is mislabeled as red and struggles to draw red items like strawberries.

“The law is so vague. They’re erring on the side of caution. But in doing so, they are going to an extreme,” Delmay told The 19th.

Cindy Nobles, president of the PFLAG chapter in Jacksonville, knows queer parents in Florida — in Duval and Clay counties — that are wary of going to parent-teacher conferences together, or even worry over how they should handle joining their children on field trips. Those parents flock to the PFLAG Jacksonville Facebook account to swap stories and seek those who understand what they’re going through. PFLAG National, which advocates for LGBTQ+ families and allied parents, has chapters across the country.

“We have same-sex couples who are afraid that they can’t go together to parent- teacher conferences,” Nobles said. “If your kid has an issue at school, do you both go talk to the counselor? It’s little things like that that are going to be big things down the road.”

What she means by little things becoming big things: Nobles’ son, who’s turning 19 this year, told her in fifth grade that he didn’t want to go back to school because he was being bullied for being gay.

“He said he was having suicidal thoughts. We brought him home. And at the end of those two years of basically virtual homeschool, now he’s socially isolated and wondering what he did wrong to make this happen to him,” Nobles said. A choice like that, made by a parent to protect their child from being discriminated against because of their LGBTQ+ identity, can mushroom into unseen consequences, she said.

“We went through that and this law wasn’t even in effect yet. So the kids that are going through school now, how are they going to be feeling? Their families are under attack, they are under attack by the head of the state.”

Jen Cousins, plaintiff in a lawsuit against the state’s “Don’t Say Gay” legislation, is familiar with the cycles of anger, disbelief, worry and horror that such legislation and other efforts against LGBTQ+ youth in Florida have caused her — so she can only imagine how much more difficult those feelings are for LGBTQ+ parents, including some of her own friends.

“It’s even harder for them because of their identities,” said Cousins, who worries about the future of her children’s lives in Florida — especially her nonbinary teenager Saffy, and her 9-year-old gay son Milo. She’s watched the toll that fighting for basic rights has taken on her friends — and she learned that her own shock at the state’s legislative efforts targeting LGBTQ+ youth did not come as a shock to her queer parent friends like it did for her.

Even as more parents have had to decide whether to uproot their families, they’ve continued to join protests against anti-LGBTQ+ legislation in Florida. More than one-fifth — 22 percent — of LGBTQ+ parents surveyed by the Williams Institute last year had joined a protest against the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, and a few said that they had become intentionally more out in response to the legislation, stressing the need to “resist” by hanging up flags at home or putting stickers on their car. Recent protests have focused on policies beyond Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law — particularly on the state’s board of medicine moving to restrict gender-affirming care for transgender youth.

Delmay says that some of his friends are considering relocating their families to more LGBTQ+ friendly states. But for him and his family, moving is out of the question.

“This is our home. Why would we leave here? I think that’s just preposterous,” Delmay said.

Perez also has no intention of moving. “My parents fled Cuba to be free. Now you’re telling me I have to leave Florida to be free? No. I’m going to stay here and I’m going to fight.”

Catholic Hospitals Barred from Offering Gender-Affirming Care

Catholic Hospitals Barred from Offering Gender-Affirming Care  Take a Deep Breath — Marriage Equality is Probably Here to Stay

Take a Deep Breath — Marriage Equality is Probably Here to Stay  Madeline Finn to Headline The East Room with Ryan Cassata & Lauren Horbal

Madeline Finn to Headline The East Room with Ryan Cassata & Lauren Horbal  Supreme Court Asked to Reconsider Landmark Same-Sex Marriage Ruling

Supreme Court Asked to Reconsider Landmark Same-Sex Marriage Ruling  Trans Youth Emergency Project Supports Trans Youth, Families

Trans Youth Emergency Project Supports Trans Youth, Families  Over a Million Queer Women Rely on Medicaid. What Happens If They Lose It?

Over a Million Queer Women Rely on Medicaid. What Happens If They Lose It?