The premier film festival has expanded from two LGBTQ features to over a dozen

By George Elkind – Photos Courtesy of Sundance Institute

Sundance’s slate of queer films has grown steadily over the years, as has the scale of the increasingly star-studded festival itself. At its founding in 1985, it wasn’t the first festival to heavily feature queer-focused works — that would be Frameline’s San Francisco International LGBTQ+ Film Festival, founded in 1977. But by steadily raising the number of queer films included (from two features in 1985 to over a dozen works in 2021), Sundance has played a crucial role in broadening the range of works made and screened for American audiences.

Before the Berlin International Film Festival and Sundance, according to film scholar and festival historian Antoine Damiens, queer films were rarely seen outside of festivals.

“It’s almost impossible to separate the history of queer cinema from film festivals: the first queer festivals — of the late 1970s — were largely started by community members and directors as a way to screen films that couldn’t be shown elsewhere,” he said. “They quickly became major actors in the economy of queer film and can be credited for creating a market for queer cinema.”

Damiens specifically links Sundance’s impact on queer cinema to a broader boom in independent filmmaking — and especially the rise of video.

“For the first time, filmmakers were able to bypass theatrical releases: distribution companies could make money by selling films directly to interested consumers. In that period, we have lots of ‘edgy’ films being made,” he said. “This new circuit of distribution pretty much changed everything for queer cinema.”

While distribution has evolved since, Sundance’s 2021 lineup stands to expand the queer film canon once again. With films like Rebecca Hall’s directorial debut “Passing,” which makes the convergence of Black women’s desires with questions of racial identity in 1929 Harlem its subject, and “4 Feet High,” about a disabled Argentinian teen interrogating her sexuality from a wheelchair, the range of experiences Sundance’s programming addresses this year continues to broaden even further.

In some ways, this isn’t unsurprising. According to LGBTQ film historian and filmmaker Jenni Olson, Sundance was always a key player in bringing greater prominence to queer works in and beyond the communities responsible for them.

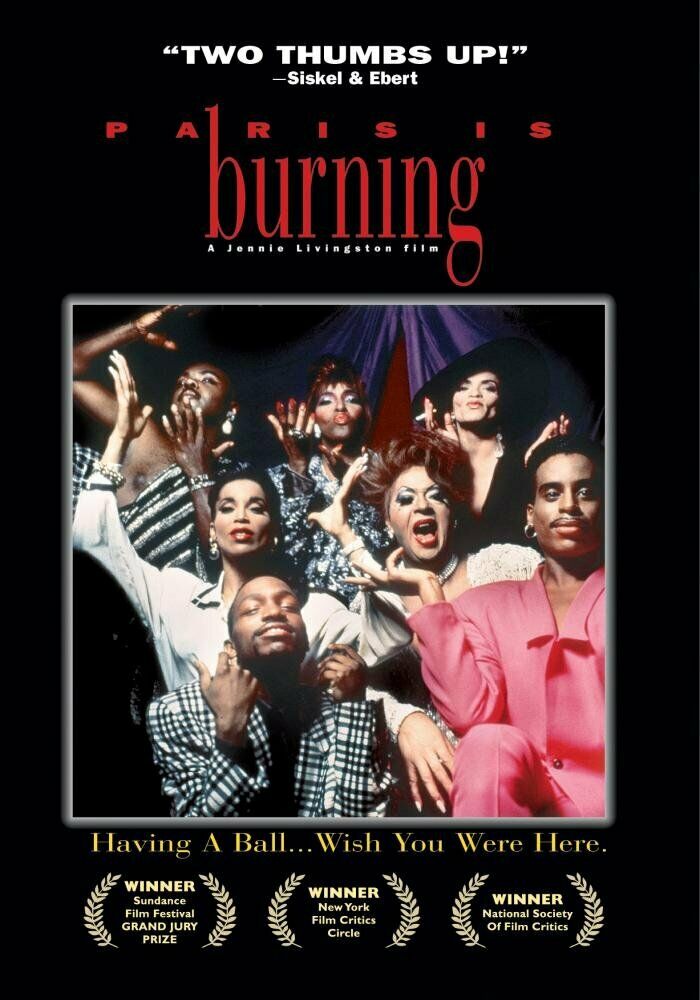

“From the very beginning, Sundance has been a bellwether — each January managing to showcase films that will end up being some of the most important LGBT films of the year,” she said. Olson specifically cites works like Oscar winner “The Times of Harvey Milk” (1985), which followed America’s first openly gay public official, and Todd Haynes’s sly, suggestive “Poison” (1991), which satirized social stigmas around sexuality via period styles and contexts. She points also to “Parting Glances” (1986), which depicted gay life in the AIDS crisis under Reagan; “Desert Hearts” (1986), which featured two women falling for one another in the American Southwest years before “Thelma and Louise” worked similar (albeit platonic) terrain, and cult-favorite “Paris is Burning” (1990), an enduring touchstone of drag culture.

The list of queer filmmakers who found boosts from or launched careers at the festival is also long: Haynes, Norman René (“Longtime Companion”), Gregg Araki (“Mysterious Skin”) and Derek Jarman (“Caravaggio”) are just a few among many.

In 1992, the proliferation of talent became so pronounced that, after a panel entitled Barbed Wire Kisses featuring a number of rising queer filmmakers, critic and scholar B. Ruby Rich dubbed the snowballing of formidable works a movement, calling it the New Queer Cinema. While the term has stuck best among academics, most have felt the movement’s force; movies as disparate as Gus Van Sant’s “Mala Noche,” Susan Seidelman’s “Desperately Seeking Susan” and Cheryl Dunye’s “The Watermelon Woman” have all helped make it up.

According to John Cooper, Sundance’s emeritus director (and the festival director from 2010-20), this progression and accumulation of queer filmmakers was not so much orchestrated as it was bound to happen as the festival sought out singular works, stories he described in a 2020 article for the Sundance Institute as “not being represented in mainstream Hollywood films” of the time. In the same piece, which recounts the history of Sundance’s queer programming, he goes on to suggest that queer films came to prominence as part of a broader wave of new independent works “not just because they represented the ‘others,’ but because they were, by nature, good and fresh and exciting.”

“Although it was a founding goal of Sundance Institute to be inclusive on every level of support for artists, the actual practice of showing diverse work has been a very organic and natural progression,” Cooper wrote. “When I think back to the original concept for both the Institute’s labs and the Festival itself, the idea was to support the most original and interesting work possible.”

This support takes a variety of forms. While programming and screening may be the most visible mode of advocacy Sundance engages in, the organization provides numerous forms of mentorship and education.

“The Sundance Institute does so much more than just showing films in the festival,” said Olson. “Their various filmmaker funding initiatives and labs are an invaluable source of support to filmmakers to make the movies in the first place. They also have a preservation initiative. And LGBT films and filmmakers are generally very well represented in these programs as well.”

Once produced and selected, premiering works at the festival offers its own host of benefits, given its role as a marketplace for distributors and a gathering place for a broad range of film professionals. Many works featured at the festival, according to Olson, go on to play a range of queer and mainstream festivals and stand a heightened chance of being picked up for broader distribution as a result.

Because the festival is in January, Olson points out that it has “always served as a launching pad for many of the biggest LGBTQ films of the year.” It also means, she notes, that programmers from major LGBTQ film festivals in San Francisco, New York and L.A. can plan ahead for their summer and fall festivals.

This early heightened visibility reached past festivals and distribution into mainstream film criticism of the time. For example, Roger Ebert praised works like 1990s “Longtime Companion” and called “The Life and Times of Harvey Milk” (which Gus Van Sant later adapted as “Milk”) “an enormously absorbing film.” But it’s hard to know if he would have seen them if not for Sundance, or if they had only played at queer festivals.

For Olson, though, showing her work at the festival — something she has done four times now — is more than just a commercial or a career opportunity: “Showing a film at Sundance is one of the most exciting experiences one can have as an independent filmmaker. Of course, partly, it’s just so exciting to be part of such a prestigious festival, but also the audiences at Sundance are passionate movie lovers who I have always found to be wonderfully responsive and interested in my work.”

Olson attributes the “major force” queer filmmakers present each year in part to the number of queer programmers present across the festival’s history (John Cooper, who began working with Sundance in 1989, is one, and Kim Yutani currently serves as the festival’s Director of Programming). Many on the programming staff and in leadership positions, too, come from the world of queer-focused film festivals: an experience that likely shapes their work.

“Sundance is about the industry — about film professionals working together, networking, buying and selling film,” said Damiens. “It’s about getting one’s film made and valued. For a queer filmmaker, it also means getting exposure and hopefully distribution in a wide variety of festivals — queer and non-queer.”

The experience of queer festivals provides, for both filmmakers and programmers, a value of its own. Olson, for instance, makes works meant chiefly for queer audiences, and considers Frameline’s San Francisco Festival as “the peak experience where I know the audience is understanding my vision in a much deeper way.”

For Damiens, queer and mainstream festival spaces are distinct from one another but strongly interconnected.

“Queer festivals are by and for the community. It’s about watching films, in the dark, with like-minded people — about seeing, in the lobby, friends and lovers; exchanging a few moments around a film with one’s community.”

Over time, both Sundance audiences and programming have evolved alongside each other, with the festival becoming more inclusive over time. While early programming often centered gay white men, Sundance’s queer programming has broadened from year to year in both tone and who it features. Compare, for instance, 1990’s “Metamorphosis: Man Into Woman,” which documented a white trans woman’s gender affirmation on video, to 2015’s unlikely breakout “Tangerine,” which more offhandedly centers two trans women of color in an iPhone-shot work that’s much more comic in tone.

In some ways, the expansion of digital filmmaking and distribution evokes the rise of video in Sundance’s early days, allowing not just for new subjects but many new directors as well. The approach has changed in part due to broader shifts in culture and filmmaking’s economic structures, according to Damiens.

“It’s definitely a different political climate: we’re no longer in the sort of sex and moral panic caused by the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the 1990s” – something Damiens cites as fueling the New Queer Cinema. “We also have a lot of queer representations on film, on TV, and online. The stakes are not as high as they used to be. There’s a lot of new channels of distribution that makes it slightly easier to direct a queer film.”

From early and ongoing efforts at foregrounding Indigenous programming to an ever-broadening array of queer films, workshops, and events — along with an increasing focus on intersectional works — Sundance has worked to stay relevant by working to reflect the breadth of filmmaking present in the world at large.

This effort goes for queer films as much as anything else. While New Queer Cinema might no longer be the word for it, Sundance’s continuing emphasis on showcasing a broader range of queer works seems both proof — and part of — a movement that is very much alive.

George Elkind is a writer and media critic based in Metro Detroit.

‘I Wish You All the Best’ Brings Tender Non-Binary Story to Digital November 25

‘I Wish You All the Best’ Brings Tender Non-Binary Story to Digital November 25  Diverse Voices, Real Stories: Tello Films’ Vision for the Future of LGBTQ+ Media

Diverse Voices, Real Stories: Tello Films’ Vision for the Future of LGBTQ+ Media  Nashville Film Festival Announces Six Captivating Feature Films Selected to Screen at the 55th Annual Event

Nashville Film Festival Announces Six Captivating Feature Films Selected to Screen at the 55th Annual Event  Call for Submissions to the 1st Annual LGBT Online Coming Out Film Festival

Call for Submissions to the 1st Annual LGBT Online Coming Out Film Festival  Nashville Film Festival Announces Sneak Peek of 54th Annual Event

Nashville Film Festival Announces Sneak Peek of 54th Annual Event  Nashville Film Festival Opens Thursday, September 29, Adds Additional Films and Special Guests

Nashville Film Festival Opens Thursday, September 29, Adds Additional Films and Special Guests