Demonstrators react during a rally in support of abortion rights in May 2022 in Seattle, Washington. (DAVID RYDER/GETTY IMAGES)

Queer legal experts are scrambling

35 states have marriage bans, and experts doubt that Congress could codify marriage equality.

By Kate Sosin, Candice Norwood

Originally published by The 19th

LGBTQ+ advocates — already exhausted from battling hundreds of anti-trans bills in states for three years — started to grapple with another reality after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade: Marriage equality now seems vulnerable to being overturned, and legal experts are unsure what could be done to protect LGBTQ+ marriage rights.

Now, queer legal experts are scrambling to put together a strategy as they debate if Congress has the authority to shore up marriage protections or if the country would revert to a 2014 patchwork, with most states outlawing LGBTQ+ marriages.

“I can’t give you an answer to that question as we have that conversation now,” said Jenny Pizer, law and policy director for Lambda Legal who was co-counsel on the 2008 California case that secured marriage equality in the state. “I’ve been practicing law now for quite a while, and we have not had this situation of rights being taken away.”

When Roe was reversed, legal experts say the court left a slate of other civil rights protections vulnerable to being thrown out — including the right to interracial marriages (Loving v. Virginia), contraception (Griswold v. Connecticut), sexual relationships for LGBTQ+ people (Lawrence v. Texas) and marriage for LGBTQ+ couples (Obergefell v. Hodges).

The right to an abortion was an unenumerated right, meaning it was not explicitly written in the Constitution and has instead been granted through the Supreme Court’s interpretation of major legal cases. Abortion, like marriage equality, access to contraception and a number of other rights, had been upheld through the 14th Amendment’s due process clause meant to protect against deprivation of the right to life, liberty and property.

A concurring opinion by Justice Clarence Thomas in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case that ultimately overturned Roe indicates he wants to reexamine whether other rights based on substantive due process have been interpreted correctly.

“In future cases, we should reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents,” Thomas wrote. Other opinions written by conservative justices show division over how the court should handle similar civil rights issues in the future.

Additionally, Thomas cited a 1997 decision on assisted suicide stating that rights that rely on due process must be “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition.” This is where Obergefell could run into trouble in the future. With the decision being only seven years old, there is no long-established tradition of marriage equality throughout the country, legal experts said.

“The Supreme Court could say, ‘We can’t find this right in the Constitution,’ which is correct, it doesn’t exist as an enumerated right. And it is absolutely not a right that is deeply rooted in the nation’s history and tradition. So they can say, ‘Let’s throw it back to the states,’” said Kimberly Mutcherson, co-dean and professor at Rutgers Law School.

Ezra Young, a visiting assistant professor at Cornell Law School, cautions that the ruling does not automatically mean that the court is preparing to scrap civil rights precedent for marginalized groups.

“This is a huge blow to disproportionately women, the vast majority are women of color or poor, [who] depend upon abortion, and all the folks who can get pregnant,” Young said. “Does this necessarily mean the court — because of Dobbs — is going to attack Obergefell, Loving, all of those things? No. That’s just what we fear they’re going to do.”

Before the Supreme Court’s 2015 ruling, LGBTQ+ advocates secured marriage equality state by state, through various legal routes. Some states passed legislation granting queer couples the right to marry. Others sent the issue to the ballot. Many took up the issue in court. But nothing was ever passed at the federal level.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi last week signaled interest in codifying abortion rights and other landmark rulings. She did not mention specific bills on marriage equality but criticized Thomas for taking aim at Obergefell.

“Legislation is being introduced to further codify freedoms which Americans currently enjoy,” she wrote in a letter.

Any potential path through Congress, however, appears tenuous. Congress has failed to pass the Equality Act, legislation that has been waiting in some form since 1974 and would grant LGBTQ+ people nationwide protection from discrimination in housing, credit and public accommodations. LGBTQ+ nondiscrimination laws tend to be easier to pass than marriage laws, and states that have both often pass discrimination protections first. Illinois passed its anti-discrimination law in 2006, seven years before passing marriage equality.

Currently, Democrats have a slim majority in the U.S. House and Senate and could stand to lose seats in the midterm elections this fall, as the president’s party often does.

Given that reality, Mutcherson believes much of the activity to protect marriage and relationship rights will happen by working at the state level to enshrine them in state constitutions, for example.

Legal experts are split on whether or not Congress would even have the authority to codify rights left vulnerable by the Dobbs decision. That’s because such issues have traditionally been under the power of states.

“Some things we as a society will be figuring out in the days to come,” Pizer said. “How much of the next chapter is written in Congress and how much is written through other political and other democratic means, I can’t tell you that right now.”

So faced with the prospect of an Obergefell overturn, advocates now find themselves staring at maps they haven’t had to look at since 2014.

“There is not a clear and easy path or one specific way that the movement would move to protect marriage,” said Fran Hutchins, executive director of the coalition of statewide LGBTQ+ advocacy organizations The Equality Federation.

From Michigan to Arizona, Colorado to Florida, 35 states have laws banning marriage equality on the books.

Naomi Goldberg is the deputy director of the Movement Advancement Project, an organization that tracks the state of LGBTQ+ rights nationwide. Goldberg has been analyzing state marriage laws in anticipation of a scenario where Obergefellis struck down.

Goldberg believes that if the Supreme Court invalidated its own marriage ruling, 32 states would revert back to banning marriage equality. Twenty-five states have banned marriage equality both in their constitutions and through their legislatures. Five block the unions only through their constitutions, and another five have done so through their statehouses. Of those, California, Iowa and Hawaii would likely continue offering marriages because their bans were either invalidated by lower courts or struck down in the legislature.

This would create a patchwork of laws around the country similar to what was in place before Obergefell, in which some states would allow marriages and others would not. LGBTQ+ advocates are confronting the reality that they may need to restart field campaigns to win support for marriage equality in states across the country. For those that have constitutional bans, most would have to send the question of marriage equality into the hands of voters via a ballot measure.

“I feel in many ways as though we’re back in 2004, in 2008, with the prospect of what it takes to have those conversations with the public to do deep public education work,” Goldberg said. “It’s an incredible investment. I feel sad that that is something we might have to do because I think there’s so many more issue areas where I want to be investing that time.”

The possible re-emergence of a system of inconsistent marriage laws around the country would be significant: Hundreds of thousands of couples have been able to legally marry as a result of Obergefell and many of these families have children. One possibility is that people’s marriages could become invalid if Obergefell is overturned, though Mutcherson notes this, “would be an outrageous move to take procedurally,” given some of the structural changes that have taken place to recognize the legitimacy of these families.

Another consequence of overturning marriage equality, Mutcherson said, is that we would end up with “a world where some same-sex couples are married and others no longer have the right to enter into marriage, which is also, I think, an untenable set of circumstances.”

“If my marriage disappears, that’s something that goes to the very heart of what it means to be a holder of rights in this country.”

Pizer believes it’s unlikely that past marriages would be invalidated, but fears the court has abandoned all precedent. As a result, she says, anything is possible for the future post-Roe.

“We now have a court that appears to be heedless in its rush to remake our society according to a very different understanding of the Constitution,” she said.

Madeline Finn to Headline The East Room with Ryan Cassata & Lauren Horbal

Madeline Finn to Headline The East Room with Ryan Cassata & Lauren Horbal  Trans Youth Emergency Project Supports Trans Youth, Families

Trans Youth Emergency Project Supports Trans Youth, Families  In Loving Memory of Phil Michal Thomas – Author, Advocate, Community Leader

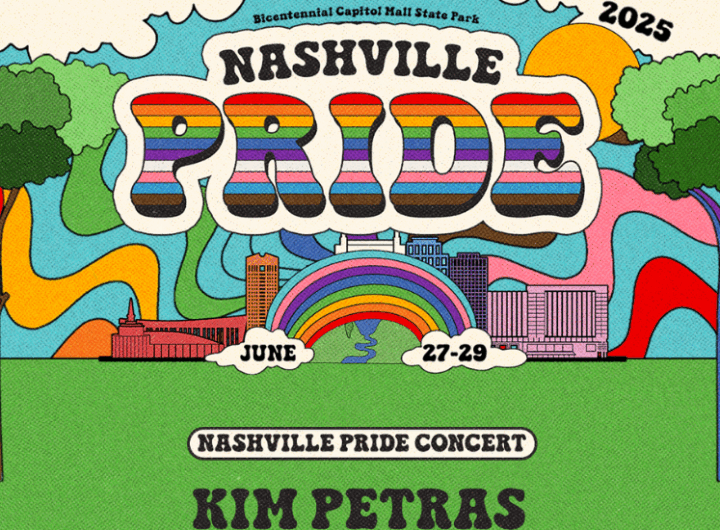

In Loving Memory of Phil Michal Thomas – Author, Advocate, Community Leader  Nashville Pride Unveils 2025 Festival Lineup: Kim Petras, 4 Non Blondes, Big Freedia & More

Nashville Pride Unveils 2025 Festival Lineup: Kim Petras, 4 Non Blondes, Big Freedia & More  Tennessee Pride Chamber Announces 12th Annual Pride In Business Awards At Saint Elle

Tennessee Pride Chamber Announces 12th Annual Pride In Business Awards At Saint Elle  Dining Out For Life® Returns To Nashville May 1

Dining Out For Life® Returns To Nashville May 1