(RENA LI FOR THE 19TH)

By Kate Sosin

Originally published by The 19th

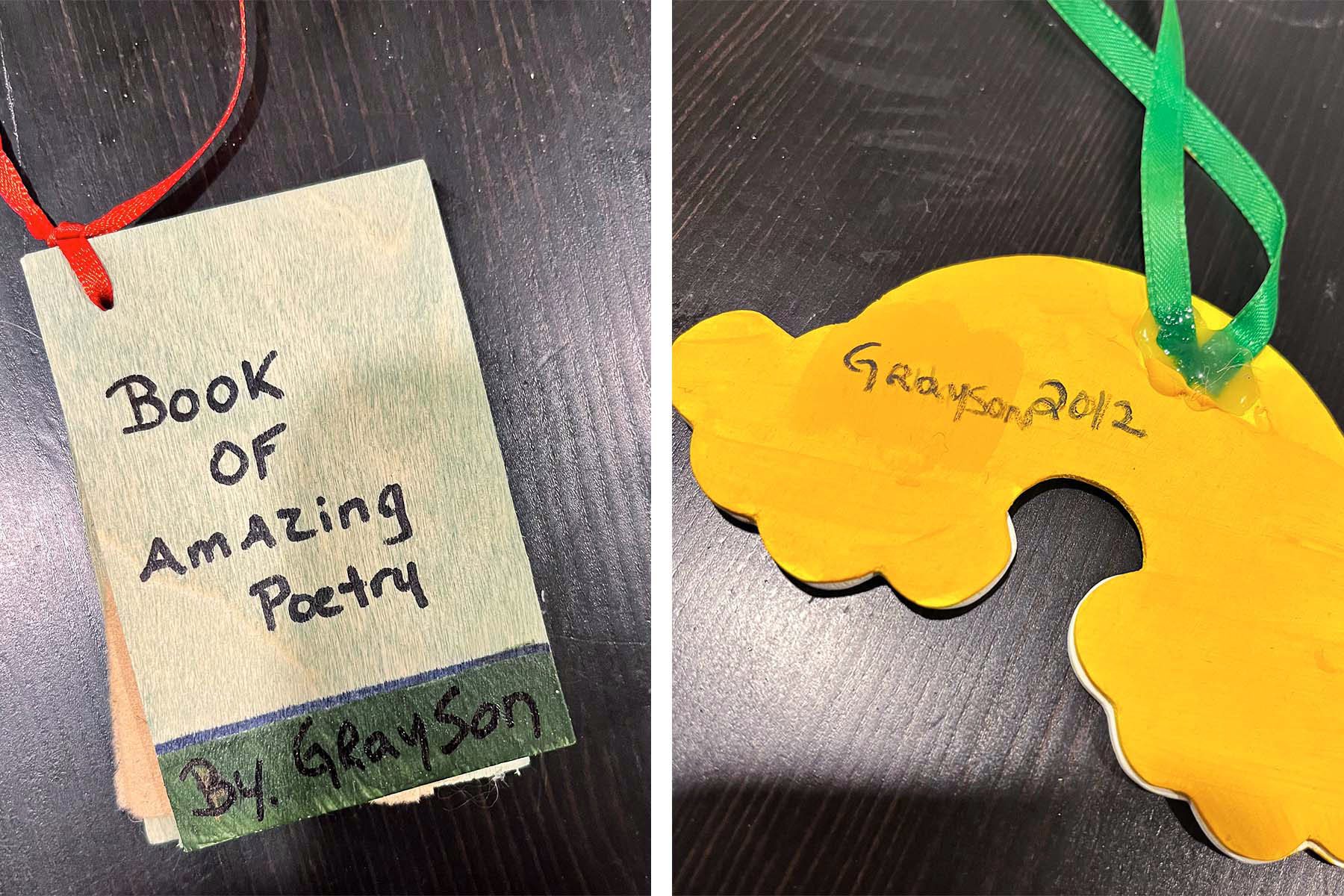

It was a box of ornaments that meant the most to Grayson Thate.

They were made of wood, glass, hot glue and string — hand-painted shapes from his childhood. He had looked at them his whole life. But that Christmas of 2017, as he unwrapped the trinkets that his mom had shipped him, he noticed something new.

“I realized that she had found a paint color that was a perfect match to each ornament, and she had painted over my deadname and replaced it with ‘Grayson,’” he said.

Deadname is what transgender people often call a name they were assigned at birth and used before transition. Thate, who was assigned female at birth but came out to his family as a man in 2017, stared down at the ornaments. There were about 30 of them in total. His mother had marked each with the year that Thate’s mother had made or bought them, as if to signal that she knew that this was who he had always been.

Thate, 23, broke down crying and called his mom.

“It wasn’t a big deal to her, like she just knew, ‘I’m giving him these ornaments to take into his home and so they’re gonna reflect who he is,’” he said. “I just felt so respected and seen by her. And then every single year when I decorate my tree, I cry every time I open them.”

Thate’s experiences do not reflect the realities for all of the estimated 1.4 million transgender people in the United States. Many head into the holidays facing difficult decisions about whether to see family either struggle or outright refuse to reflect who they are, from using their names and pronouns to misgendering them in conversation.

Amy Green, the vice president of research for LGBTQ+ youth crisis organization the Trevor Project, says the season can be particularly difficult for queer youth living at home, who don’t have the option of skipping family gatherings.

“The holiday season is generally thought of to be a joyous time when folks gather around with loved ones to celebrate, but for many trans and nonbinary youth, it can be a really emotional and stressful time, as they may be around family members and conversations that don’t align with who they are,” Green said.

Last year, the Trevor Project reported that 40 percent of LGBTQ+ youth had “seriously considered” suicide, and that just 1 in 5 trans and nonbinary youth said their identities were widely respected by the people in their lives.

For those whose families do support them, the result can be lifesaving, the organization found.

Earlier this year, the group released another study that found that trans and nonbinary kids who were accepted by just one adult were 33 percent less likely to report a suicide attempt in a year.

“Those conversations where parents may try to attempt to convince their child that they’re not trans or they can’t be trans or they can’t be queer, those are often done out of that fear of how the world would treat those youth,” Green said. “When parents are able instead to unequivocally accept, affirm, love and support their youth, that’s really the most important factor.”

The same is also true for adults, Green said.

Dr. Liz Powell, a genderqueer psychologist, knows this well. They have advised patients through such moments and also lived through them, navigating coming out to their own mom and checking their nonbinary identity at the door to get through the holidays.

Powell said when they came out to their mom as bisexual at age 17, the conversation went awry.

“She asked me if I had sex with trees or animals because if you’re bisexual obviously you have sex with everything,” said Powell, who is now 39. A conversation about the fact that Powell is polyamorous went similarly badly. So, the Philadelphia resident decided not to bridge gender fluidity with their mom.

“I would rather just be misgendered for the week that I was at home and deal with that than try to get through a conversation about gender and especially nonbinary genders with my mom,” Powell said. “I think, for me, it’s a big debate of, what resources do I have?”

That doesn’t mean their mom doesn’t know they are genderqueer.

“I know she stalks my social media,” Powell said. Before Powell saw their mom at Thanksgiving, their mom made a few comments about nonbinary identity that made Powell hopeful that she had picked up the right lingo.

“But once I got there, it was all she/her/woman stuff,” Powell said.

Eric Anthony Grollman has studied the health impacts of discrimination on trans and nonbinary people extensively as an associate professor at the University of Richmond. Grollman said research suggests that familial rejection can be particularly devastating for gender-diverse people of all ages.

“I wouldn’t frame this as discrimination per se,” they said. “What we talk about is rejection, and maybe violence or abuse. …The parallel between them is that you are being treated in a negative or disrespectful way solely because of who you are.”

According to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, 60 percent of transgender people who did come out to their immediate families said those families were supportive, but 10 percent of those surveyed reported their family members were physically violent toward them because they are trans.

Grollman added that even small slights or instances of transphobia from family can compound for youth.

“Unfortunately, what seems like, ‘Oh, it’s not a big deal,’ is one of several instances of invalidation that trans people are experiencing,” Grollman said. “There’s a greater urgency in actually being respectful and affirming and validating.”

Grollman contends that urgency is not just about mental health. Their research links discrimination and family rejection to worse health outcomes for trans people, including higher rates of suicidality and substance abuse.

But for all of the data that shows troubling health outcomes among transgender people, Green says another story is just as possible. Trevor Project’s data has shown that among families who embrace their gender-diverse family members, rates of suicidality level out to be just about even with their cisgender peers.

Of course, not all methods of affirming trans family members are perfect. That Christmas of 2017, Thate’s little sister slipped a “best brother” mug into his stocking. The gesture warmed his heart. “But my older brother was very offended by that,” he said, laughing.

For families looking for advice on how to be an ally to their trans or nonbinary youth, the Trevor Project has a guide.

Catholic Hospitals Barred from Offering Gender-Affirming Care

Catholic Hospitals Barred from Offering Gender-Affirming Care  Madeline Finn to Headline The East Room with Ryan Cassata & Lauren Horbal

Madeline Finn to Headline The East Room with Ryan Cassata & Lauren Horbal  Trans Youth Emergency Project Supports Trans Youth, Families

Trans Youth Emergency Project Supports Trans Youth, Families  Over a Million Queer Women Rely on Medicaid. What Happens If They Lose It?

Over a Million Queer Women Rely on Medicaid. What Happens If They Lose It?  In Loving Memory of Phil Michal Thomas – Author, Advocate, Community Leader

In Loving Memory of Phil Michal Thomas – Author, Advocate, Community Leader  What’s Going On at Vanderbilt? Transgender Health Services Quietly Shut Down

What’s Going On at Vanderbilt? Transgender Health Services Quietly Shut Down